16 Spatial Regression

Even though it may be tempting to focus on interpreting the map pattern of an areal support response variable of interest, the pattern may largely derive from covariates (and their functional forms), as well as the respective spatial footprints of the variables in play. Spatial autoregressive models in two dimensions began without covariates and with clear links to time series (Whittle 1954). Extensions included tests for spatial autocorrelation in linear model residuals, and models applying the autoregressive component to the response or the residuals, where the latter matched the tests for residuals (Cliff and Ord 1972, 1973). These “lattice” models of areal data typically express the dependence between observations using a graph of neighbours in the form of a contiguity matrix.

Of course, handling a spatial correlation structure in a generalised least squares model or a (generalised) linear or non-linear mixed effects model such as those provided in the nlme and many other packages does not have to use a graph of neighbours (Pinheiro and Bates 2000). These models are also spatial regression models, using functions of the distance between observations, and fitted variograms to model the spatial autocorrelation present; such models have been held to yield a clearer picture of the underlying processes (Wall 2004), building on geostatistics. For example, the glmmTMB package successfully uses this approach to spatial regression (Brooks et al. 2017). Here we will only consider spatial regression using spatial weights matrices.

16.1 Markov random field and multilevel models

There is a large literature in disease mapping using conditional autoregressive (CAR) and intrinsic CAR (ICAR) models in spatially structured random effects. These extend to multilevel models, in which the spatially structured random effects may apply at different levels of the model (Bivand et al. 2017). In order to try out some of the variants, we need to remove the no-neighbour observations from the tract level, and from the model output zone aggregated level, in two steps as reducing the tract level induces a no-neighbour outcome at the model output zone level. Many of the model estimating functions take family arguments, and fit generalised linear mixed effects models with per-observation spatial random effects structured using a Markov random field representation of relationships between neighbours. In the multilevel case, the random effects may be modelled at the group level, which is the case presented in the following examples.

We follow Gómez-Rubio (2019) in summarising Pinheiro and Bates (2000) and McCulloch and Searle (2001) to describe the mixed-effects model representation of spatial regression models. In a Gaussian linear mixed model setting, a random effect \(u\) is added to the model, with response \(Y\), fixed covariates \(X\), their coefficients \(\beta\) and error term \(\varepsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2), i=1,\dots, n\):

\[ Y = X \beta + Z u + \varepsilon \] \(Z\) is a fixed design matrix for the random effects. If there are \(n\) random effects, it will be an \(n \times n\) identity matrix if instead the observations are aggregated into \(m\) groups, so with \(m < n\) random effects, it will be an \(n \times m\) matrix showing which group each observation belongs to. The random effects are modelled as a multivariate Normal distribution \(u \sim N(0, \sigma^2_u \Sigma)\), and \(\sigma^2_u \Sigma\) is the square variance-covariance matrix of the random effects.

A division has grown up, possibly unhelpfully, between scientific fields using CAR models (Besag 1974), and simultaneous autoregressive models (SAR) (Ord 1975; Hepple 1976). Although CAR and SAR models are closely related, these fields have found it difficult to share experience of applying similar models, often despite referring to key work summarising the models (Ripley 1981, 1988; Cressie 1993). Ripley gives the SAR variance as (Ripley 1981, 89), here shown as the inverse \(\Sigma^{-1}\) (also known as the precision matrix):

\[ \Sigma^{-1} = [(I - \rho W)'(I - \rho W)] \]

where \(\rho\) is a spatial autocorrelation parameter and \(W\) is a non-singular spatial weights matrix that represents spatial dependence. The CAR variance is:

\[ \Sigma^{-1} = (I - \rho W) \] where \(W\) is a symmetric and strictly positive definite spatial weights matrix. In the case of the intrinsic CAR model, avoiding the estimation of a spatial autocorrelation parameter, we have:

\[ \Sigma^{-1} = M = \mathrm{diag}(n_i) - W \] where \(W\) is a symmetric and strictly positive definite spatial weights matrix as before and \(n_i\) are the row sums of \(W\). The Besag-York-Mollié model includes intrinsic CAR spatially structured random effects and unstructured random effects. The Leroux model combines matrix components for unstructured and spatially structured random effects, where the spatially structured random effects are taken as following an intrinsic CAR specification:

\[ \Sigma^{-1} = [(1 - \rho) I_n + \rho M] \] References to the definitions of these models may be found in Gómez-Rubio (2020), and estimation issues affecting the Besag-York-Mollié and Leroux models are reviewed by Gerber and Furrer (2015).

More recent books expounding the theoretical bases for modelling with areal data simply point out the similarities between SAR and CAR models in relevant chapters (Gaetan and Guyon 2010; Van Lieshout 2019); the interested reader is invited to consult these sources for background information.

Boston house value dataset

Here we shall use the Boston housing dataset, which has been restructured and furnished with census tract boundaries (Bivand 2017). The original dataset used 506 census tracts and a hedonic model to try to estimate willingness to pay for clean air. The response was constructed from counts of ordinal answers to a 1970 census question about house value. The response is left- and right-censored in the census source and has been treated as Gaussian. The key covariate was created from a calibrated meteorological model showing the annual nitrogen oxides (NOX) level for a smaller number of model output zones. The numbers of houses responding also varies by tract and model output zone. There are several other covariates, some measured at the tract level, some by town only, where towns broadly correspond to the air pollution model output zones.

We can start by reading in the 506 tract dataset from spData (Bivand, Nowosad, and Lovelace 2022), and creating a contiguity neighbour object and from that again a row standardised spatial weights object.

If we examine the median house values, we find that those for censored values have been assigned as missing, and that 17 tracts are affected.

table(boston_506$censored)

#

# left no right

# 2 489 15summary(boston_506$median)

# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

# 5600 16800 21000 21749 24700 50000 17Next, we can subset to the remaining 489 tracts with non-censored house values, and the neighbour object to match. The neighbour object now has one observation with no neighbours.

boston_506$CHAS <- as.factor(boston_506$CHAS)

boston_489 <- boston_506[!is.na(boston_506$median),]

nb_q_489 <- spdep::poly2nb(boston_489)

# Warning in spdep::poly2nb(boston_489): some observations have no neighbours;

# if this seems unexpected, try increasing the snap argument.

# Warning in spdep::poly2nb(boston_489): neighbour object has 3 sub-graphs;

# if this sub-graph count seems unexpected, try increasing the snap argument.

lw_q_489 <- spdep::nb2listw(nb_q_489, style = "W",

zero.policy = TRUE)The NOX_ID variable specifies the upper-level aggregation, letting us aggregate the tracts to air pollution model output zones. We can create aggregate neighbour and row standardised spatial weights objects, and aggregate the NOX variable taking means, and the CHAS Charles River dummy variable for observations on the river. Here we follow the principles outlined in Section 5.3.1 for spatially extensive and intensive variables; neither NOX nor CHAS can be summed, as they are not count variables.

agg_96 <- list(as.character(boston_506$NOX_ID))

boston_96 <- aggregate(boston_506[, "NOX_ID"], by = agg_96,

unique)

nb_q_96 <- spdep::poly2nb(boston_96)

lw_q_96 <- spdep::nb2listw(nb_q_96)

boston_96$NOX <- aggregate(boston_506$NOX, agg_96, mean)$x

boston_96$CHAS <-

aggregate(as.integer(boston_506$CHAS)-1, agg_96, max)$xThe response is aggregated using the weightedMedian function in matrixStats, and midpoint values for the house value classes. Counts of houses by value class were punched to check the published census values, which can be replicated using weightedMedian at the tract level. Here we find two output zones with calculated weighted medians over the upper census question limit of USD $50,000, and remove them subsequently as they also are affected by not knowing the appropriate value to insert for the top class by value. This is a case of spatially extensive aggregation, for which the summation of counts is appropriate:

nms <- names(boston_506)

ccounts <- 23:31

for (nm in nms[c(22, ccounts, 36)]) {

boston_96[[nm]] <- aggregate(boston_506[[nm]], agg_96, sum)$x

}

br2 <-

c(3.50, 6.25, 8.75, 12.5, 17.5, 22.5, 30, 42.5, 60) * 1000

counts <- as.data.frame(boston_96)[, nms[ccounts]]

f <- function(x) matrixStats::weightedMedian(x = br2, w = x,

interpolate = TRUE)

boston_96$median <- apply(counts, 1, f)

is.na(boston_96$median) <- boston_96$median > 50000

summary(boston_96$median)

# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

# 9009 20417 23523 25263 30073 49496 2Before subsetting, we aggregate the remaining covariates by weighted mean using the tract population counts punched from the census (Bivand 2017); these are spatially intensive variables, not count data.

POP <- boston_506$POP

f <- function(x) matrixStats::weightedMean(x[,1], x[,2])

for (nm in nms[c(9:11, 14:19, 21, 33)]) {

s0 <- split(data.frame(boston_506[[nm]], POP), agg_96)

boston_96[[nm]] <- sapply(s0, f)

}

boston_94 <- boston_96[!is.na(boston_96$median),]

nb_q_94 <- spdep::subset.nb(nb_q_96, !is.na(boston_96$median))

lw_q_94 <- spdep::nb2listw(nb_q_94, style="W")We now have two datasets at each level, at the lower, census tract level, and at the upper, air pollution model output zone level, one including the censored observations, the other excluding them.

boston_94a <- aggregate(boston_489[,"NOX_ID"],

list(boston_489$NOX_ID), unique)

nb_q_94a <- spdep::poly2nb(boston_94a)

# Warning in spdep::poly2nb(boston_94a): some observations have no neighbours;

# if this seems unexpected, try increasing the snap argument.

# Warning in spdep::poly2nb(boston_94a): neighbour object has 2 sub-graphs;

# if this sub-graph count seems unexpected, try increasing the snap argument.

NOX_ID_no_neighs <-

boston_94a$NOX_ID[which(spdep::card(nb_q_94a) == 0)]

boston_487 <- boston_489[is.na(match(boston_489$NOX_ID,

NOX_ID_no_neighs)),]

boston_93 <- aggregate(boston_487[, "NOX_ID"],

list(ids = boston_487$NOX_ID), unique)

row.names(boston_93) <- as.character(boston_93$NOX_ID)

nb_q_93 <- spdep::poly2nb(boston_93,

row.names = unique(as.character(boston_93$NOX_ID)))The original model related the log of median house values by tract to the square of NOX values, including other covariates usually related to house value by tract, such as aggregate room counts, aggregate age, ethnicity, social status, distance to downtown and to the nearest radial road, a crime rate, and town-level variables reflecting land use (zoning, industry), taxation and education (Bivand 2017). This structure will be used here to exercise issues raised in fitting spatial regression models, including the presence of multiple levels.

16.2 Multilevel models of the Boston dataset

The ZN, INDUS, NOX, RAD, TAX, and PTRATIO variables show effectively no variability within the TASSIM zones, so in a multilevel model the random effect may absorb their influence.

IID random effects with lme4

The lme4 package (Bates et al. 2022) lets us add an independent and identically distributed (IID) unstructured random effect at the model output zone level by updating the model formula with a random effects term:

Copying the random effect into the "sf" object for mapping is performed below.

boston_93$MLM_re <- ranef(MLM)[[1]][,1]IID and CAR random effects with hglm

The same model may be estimated using the hglm package (Alam, Ronnegard, and Shen 2019), which also permits the modelling of discrete responses, this time using an extra one-sided formula to express the random effects term:

library(hglm) |> suppressPackageStartupMessages()

suppressWarnings(HGLM_iid <- hglm(fixed = form,

random = ~1 | NOX_ID,

data = boston_487,

family = gaussian()))

boston_93$HGLM_re <- unname(HGLM_iid$ranef)The same package has been extended to spatially structured SAR and CAR random effects, for which a sparse spatial weights matrix is required (Alam, Rönnegård, and Shen 2015); we choose binary spatial weights:

library(spatialreg)

W <- as(spdep::nb2listw(nb_q_93, style = "B"), "CsparseMatrix")We fit a CAR model at the upper level, using the rand.family argument, where the values of the indexing variable NOX_ID match the row names of \(W\):

suppressWarnings(HGLM_car <- hglm(fixed = form,

random = ~ 1 | NOX_ID,

data = boston_487,

family = gaussian(),

rand.family = CAR(D=W)))

boston_93$HGLM_ss <- HGLM_car$ranef[,1]IID and ICAR random effects with R2BayesX

The R2BayesX package (Umlauf et al. 2022) provides flexible support for structured additive regression models, including spatial multilevel models. The models include an IID unstructured random effect at the upper level using the "re" specification in the sx model term (Umlauf et al. 2015); we choose the "MCMC" method:

library(R2BayesX) |> suppressPackageStartupMessages()boston_93$BX_re <- BX_iid$effects["sx(NOX_ID):re"][[1]]$Meanand the "mrf" (Markov Random Field) spatially structured intrinsic CAR random effect specification based on a graph derived from converting a suitable "nb" object for the upper level. The "region.id" attribute of the "nb" object needs to contain values corresponding to the indexing variable in the sx effects term, to facilitate the internal construction of design matrix \(Z\):

As we saw above in the intrinsic CAR model definition, the counts of neighbours are entered on the diagonal, but the current implementation uses a dense, not sparse, matrix:

The sx model term continues to include the indexing variable, and now passes through the intrinsic CAR precision matrix:

boston_93$BX_ss <- BX_mrf$effects["sx(NOX_ID):mrf"][[1]]$MeanIID, ICAR and Leroux random effects with INLA

Bivand, Gómez-Rubio, and Rue (2015) and Gómez-Rubio (2020) present the use of the INLA package (Rue, Lindgren, and Teixeira Krainski 2022) and the inla model fitting function with spatial regression models:

library(INLA) |> suppressPackageStartupMessages()Although differing in details, the approach by updating the fixed model formula with an unstructured random effects term is very similar to that seen above:

boston_93$INLA_re <- INLA_iid$summary.random$NOX_ID$meanAs with most implementations, care is needed to match the indexing variable with the spatial weights; in this case using indices \(1, \dots, 93\) rather than the NOX_ID variable directly:

ID2 <- as.integer(as.factor(boston_487$NOX_ID))The same sparse binary spatial weights matrix is used, and the intrinsic CAR representation is constructed internally:

boston_93$INLA_ss <- INLA_ss$summary.random$ID2$meanThe sparse Leroux representation as given by Gómez-Rubio (2020) can be constructed in the following way:

This model can be estimated using the "generic1" model with the specified precision matrix:

boston_93$INLA_lr <- INLA_lr$summary.random$ID2$meanICAR random effects with mgcv::gam()

In a very similar way, the gam function in the mgcv package (Wood 2022) can take an "mrf" term using a suitable "nb" object for the upper level. In this case the "nb" object needs to have the contents of the "region.id" attribute copied as the names of the neighbour list components, and the indexing variable needs to be a factor (Wood 2017):

The specification of the spatially structured term again differs in details from those above, but achieves the same purpose. The "REML" method of bayesx gives the same results as gam using "REML" in this case:

The upper-level random effects may be extracted by predicting terms; as we can see, the values in all lower-level tracts belonging to the same upper-level air pollution model output zones are identical:

so we can return the first value for each upper-level unit:

Upper-level random effects: summary

In the cases of hglm, bayesx, inla and gam, we could also model discrete responses without further major difficulty, and bayesx, inla and gam also facilitate the generalisation of functional form fitting for included covariates.

Unfortunately, the coefficient estimates for the air pollution variable for these multilevel models are not helpful. All are negative as expected, but the inclusion of the model output zone level effects, IID or spatially structured, makes it is hard to disentangle the influence of the scale of observation from that of covariates observed at that scale rather than at the tract level.

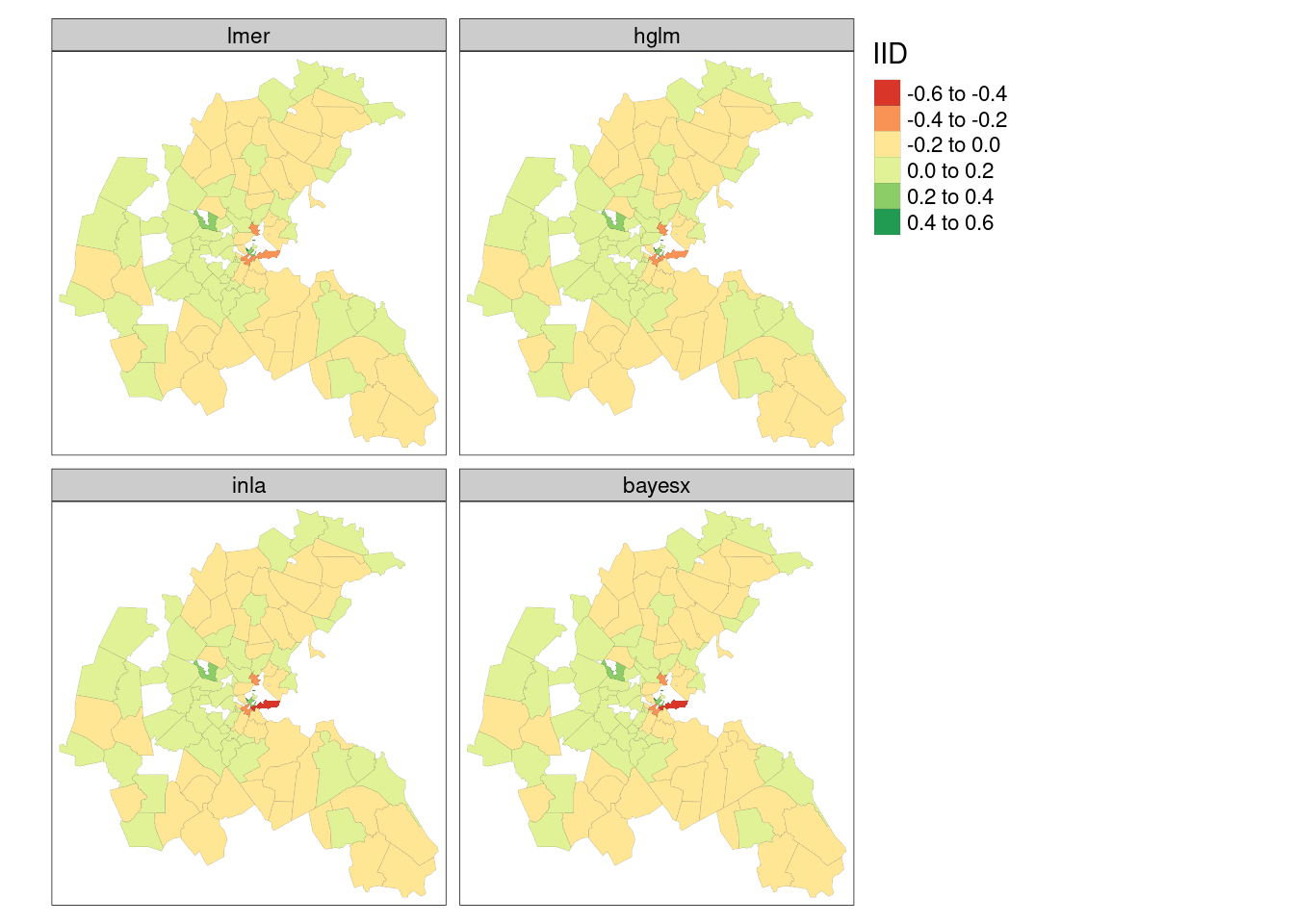

Figure 16.1 shows that the air pollution model output zone level IID random effects are very similar across the four model fitting functions reported. In all the maps, the central downtown zones have stronger negative random effect values, but strong positive values are also found in close proximity; suburban areas take values closer to zero.

Code

library(tmap, warn.conflicts=FALSE)

tmap4 <- packageVersion("tmap") >= "3.99"

if (tmap4) {

tm_shape(boston_93) +

tm_polygons(fill = c("MLM_re", "HGLM_re", "INLA_re", "BX_re"),

fill.legend = tm_legend("IID", frame=FALSE, item.r = 0),

fill.free = FALSE, lwd = 0.01,

fill.scale = tm_scale(midpoint = 0, values = "brewer.rd_yl_gn")) +

tm_facets_wrap(columns = 2, rows = 2) +

tm_layout(panel.labels = c("lmer", "hglm", "inla", "bayesx"))

} else {

tm_shape(boston_93) +

tm_fill(c("MLM_re", "HGLM_re", "INLA_re", "BX_re"),

midpoint = 0, title = "IID") +

tm_facets(free.scales = FALSE) +

tm_borders(lwd = 0.3, alpha = 0.4) +

tm_layout(panel.labels = c("lmer", "hglm", "inla", "bayesx"))

}

log(median) is 2.1893

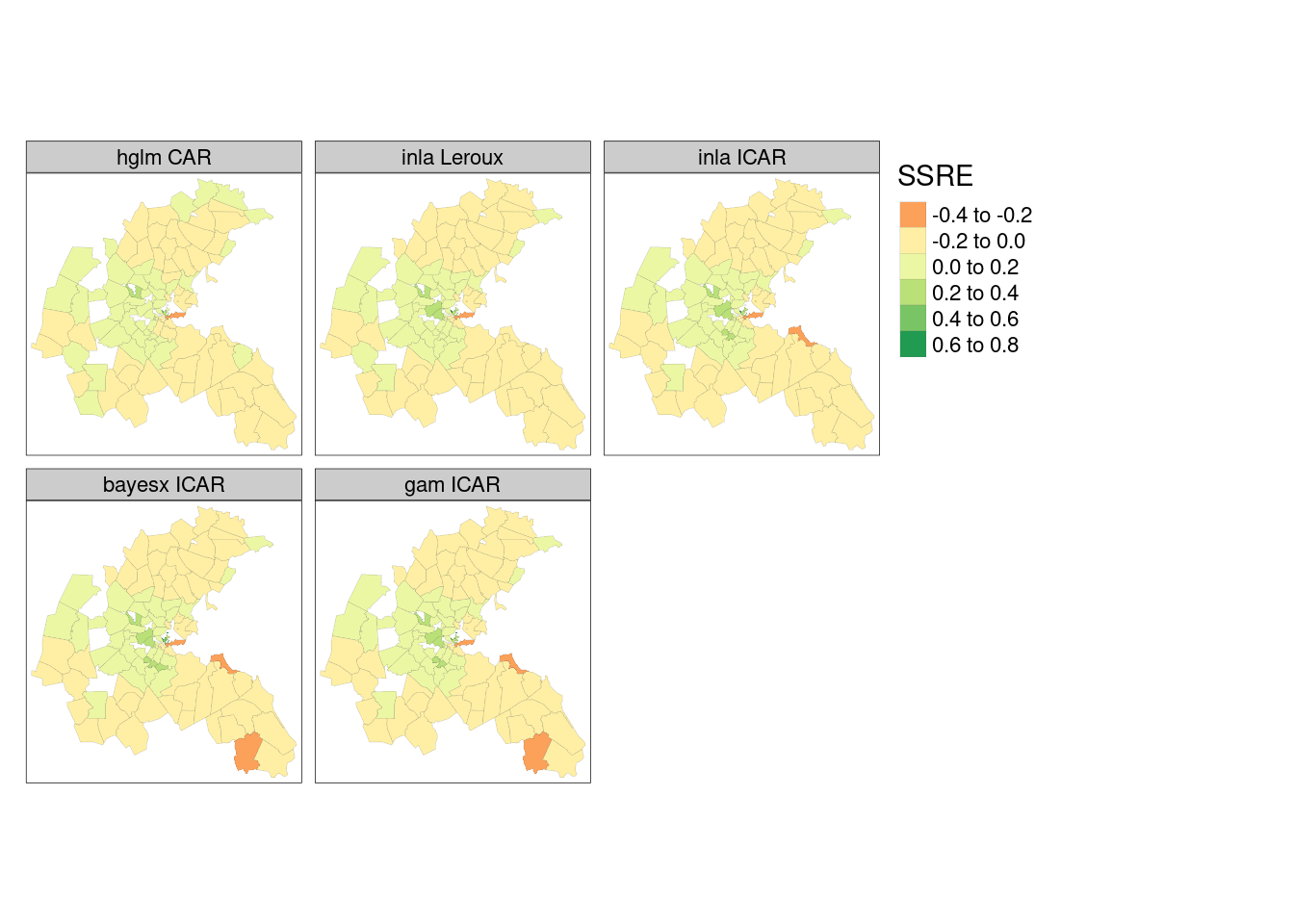

Figure 16.2 shows that the spatially structured random effects are also very similar to each other, with the "SAR" spatial smooth being perhaps a little smoother than the "CAR" smooths when considering the range of values taken by the random effect term.

Code

if (tmap4) {

tm_shape(boston_93) +

tm_polygons(fill = c("HGLM_ss", "INLA_lr", "INLA_ss", "BX_ss",

"GAM_ss"),

fill.legend = tm_legend("SSRE", frame=FALSE, item.r = 0),

fill.free = FALSE, lwd = 0.1,

fill.scale = tm_scale(midpoint = 0, values = "brewer.rd_yl_gn")) +

tm_facets_wrap(columns = 3, rows = 2) +

tm_layout(panel.labels = c("hglm CAR", "inla Leroux",

"inla ICAR", "bayesx ICAR", "gam ICAR"))

} else {

tm_shape(boston_93) +

tm_fill(c("HGLM_ss", "INLA_lr", "INLA_ss", "BX_ss",

"GAM_ss"), midpoint = 0, title = "SSRE") +

tm_facets(free.scales = FALSE) +

tm_borders(lwd = 0.3, alpha = 0.4) +

tm_layout(panel.labels = c("hglm CAR", "inla Leroux",

"inla ICAR", "bayesx ICAR", "gam ICAR"))

}

Although there is still a great need for more thorough comparative studies of model fitting functions for spatial regression including multilevel capabilities, there has been much progress over recent years. Vranckx, Neyens, and Faes (2019) offer a recent comparative survey of disease mapping spatial regression, typically set in a Poisson regression framework offset by an expected count. In Bivand and Gómez-Rubio (2021), methods for estimating spatial survival models using spatial weights matrices are compared with spatial probit models.

16.3 Exercises

- Construct a multilevel dataset using the Athens housing data from the archived HSAR package: https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/HSAR/HSAR_0.5.1.tar.gz, and included in spData from version 2.2.1. At which point do the municipality department attribute values get copied out to all the point observations within each municipality department?

- Create neighbour objects at both levels. Test

greenspfor spatial autocorrelation at the upper level, and then at the lower level. What has been the chief consequence of copying out the area of green spaces in square meters for the municipality departments to the point support property level? - Using the formula object from the vignette, assess whether adding the copied out upper-level variables seems sensible. Use

mgcv::gamto fit a linear mixed effects model (IID ofnum_depidentifying the municipality departments) using just the lower-level variables and the lower- and upper-level variables. Do your conclusions differ? - Complete the analysis by replacing the IID random effects with an

"mrf"Markov random field and the contiguity neighbour object created above. Do you think that it is reasonable to, for example, draw any conclusions based on the municipality department level variables such asgreensp?